Glassfish Example

Here is a real example of some code that does that, namely Glassfish 4.1 does not run on JDK nine because the JVM throws an IllegalAccessError

The error message is

class com.sun.enterprise.security.provider policy wrapper

com.sun.security.provider policy file

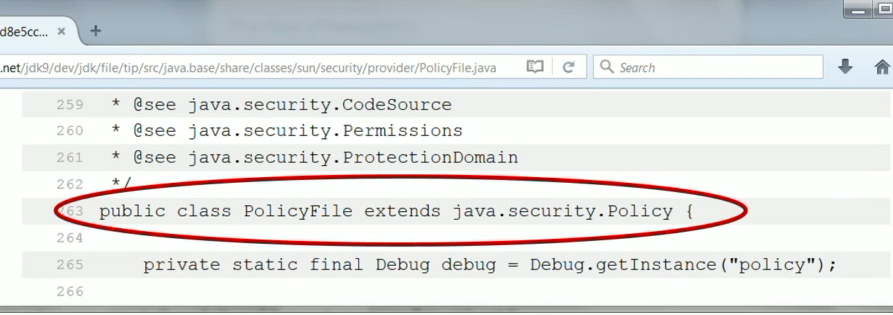

Now a glance at the open JDK repository shows us that the policy file class in sun.security is declared public, but because that package is not exported by java.base, policy file is only accessible from code in java.base itself.

263 public class PolicyFile extends java.security.Policy {

Additional context from the image:

* This code appears in a file named `PolicyFile.java` under the package path:

jdk9/dev/jdk/file/tip/src/java.base/share/classes/sun/security/provider/

* Preceding lines contain Javadoc `@see` tags referencing:

* @see java.security.CodeSource

* @see java.security.Permissions

* @see java.security.ProtectionDomain

* The following line in the file reads:

private static final Debug debug = Debug.getInstance("policy");

To be clear in JDK 9, the GlassFish code cannot access this public policy file class at compile time or runtime.

It is exactly like trying to access a "package private" class.

javac gives an error and the virtual machine throws IllegalAccessError.

GlassFish will have to find a supported API, not one of these concealed sun.* API's.

Reusing a Module

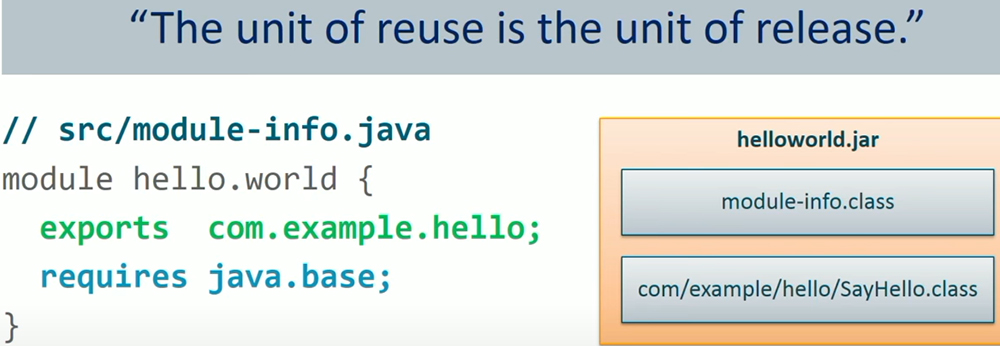

module exports packages, but requires modules

I would like to return to the

module-info.java

It is really important to understand that a module

- exports packages,

- but requires modules.

> “The unit of reuse is the unit of release.”

Java code (from `src/module-info.java`):

module hello.world {

exports com.example.hello;

requires java.base;

}

Diagram of compiled JAR (helloworld.jar):

helloworld.jar

- module-info.class

- com/example/hello/SayHello.class

The "unit of reuse" is the "unit of release".

In the Java Platform Module System (JPMS), the `module-info.java` file acts like a manifest for a module — it declares what the module provides to others and what it needs to function.

In your example:

In your example:

module hello.world {

exports com.example.hello;

requires java.base;

}

module hello.world { ... }- Declares a module named

hello.world. - A module is a self-contained collection of packages, classes, and resources.

- The name

hello.worldmust match the logical module name used in themodule-path.

- Declares a module named

exports com.example.hello;- Exports the package

com.example.helloso other modules can access its public types. - Without this line,

com.example.hellowould be internal to thehello.worldmodule, even if its classes arepublic. - Exporting a package is selective visibility control — you choose which packages in your module are available externally.

- Exports the package

requires java.base;- Declares a dependency on another module.

java.baseis the core module in Java (containsjava.lang,java.util,java.io, etc.).- All modules automatically require

java.baseimplicitly, so explicitly writing it here is optional — it’s included for clarity.

How JPMS Uses This Information

When compiling or running:

- The compiler and JVM use the

module-info.class(compiled frommodule-info.java) to enforce strong encapsulation. - At runtime, the module system ensures:

- You can only access packages that another module exports.

- You can only use modules you explicitly require.